The Design Museum spotlights music technology history

The London exhibition at the intersection of electronic music and design.

Words: Bruce Tantum

At their core, design and music share a lot of the same processes and goals. Both art forms involve taking a handful of core elements (in music’s case, sounds, notes, volume and the like), and in arranging those elements in just the right way to get the desired result. But specifically, the relationship between design and electronic music feels particularly strong, for another reason: Brilliant design can be used to express the ineffable joys of electronic music far better than can words, or anything else but the music itself. “Because it is so abstract, electronic music needs to collaborate with design in order to present itself to the world,” says Gemma Curtain, a curator at London’s Design Museum. So it makes sense that the museum is currently hosting Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers, an essential exhibition that focuses on that relationship.

Despite the exhibition’s moniker, the era covered by the show actually begins prior to Kraftwerk’s early-’70s transition into pure electronics. A handy timeline charting electronic music’s embryonic burbles back in 1901, and a bit of museum space is given over chronicling the work of synthesizer trailblazers like Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire; of particular interest are early electronic instruments like the Croix Sonore and the Ondes Martenot, along with later oddities such as the Gmebaphone2. But the real focus of the exhibit begins with Kraftwerk — the group’s goofy version of futurism provided fertile ground for creative design work. Take time to sample the charming and effective 3D animation that’s accompanied their live dates.

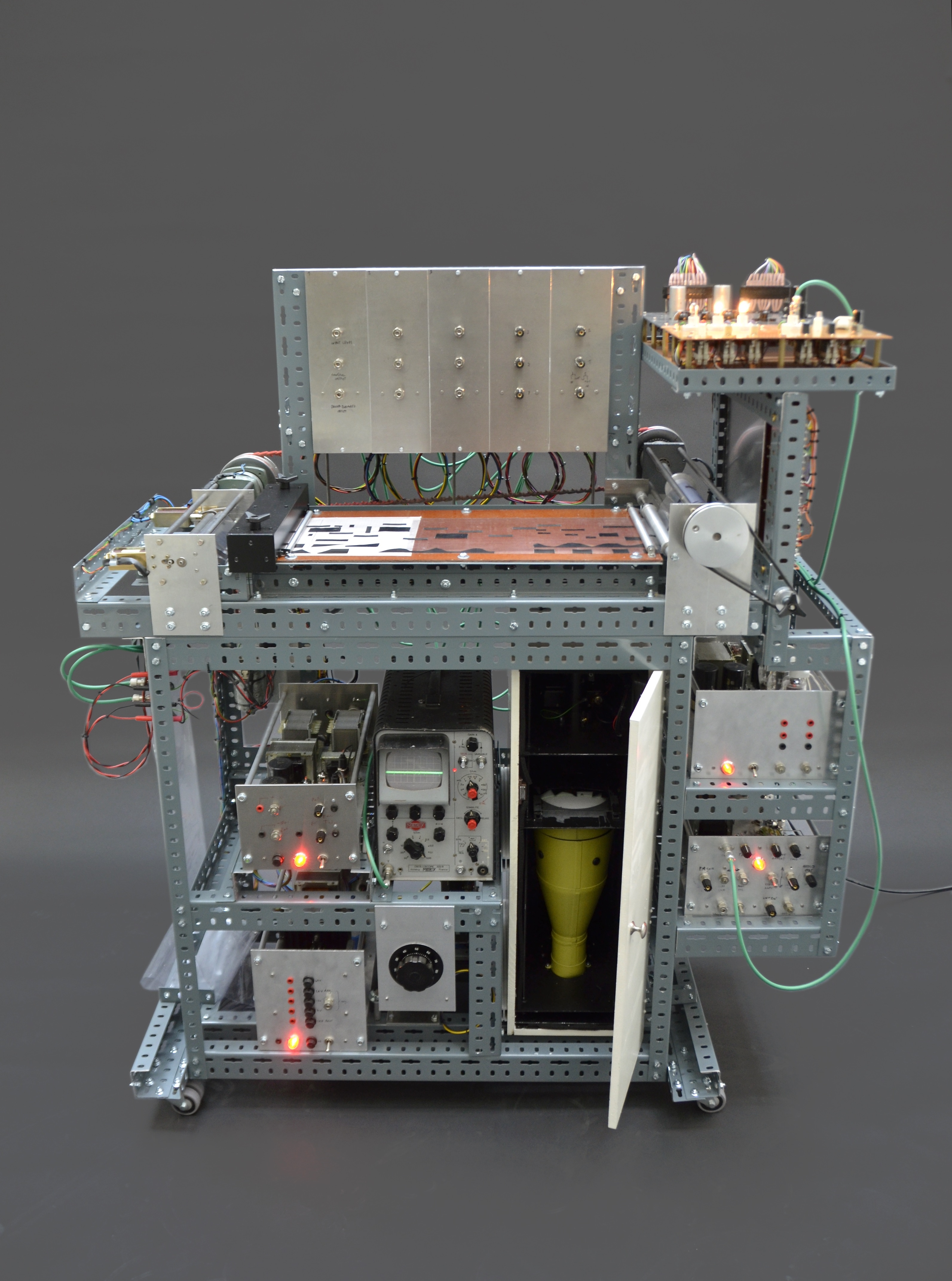

Jean-Michel Jarre’s ‘imagined’ studio, on display at The Design Museum in London. Photo: Gil Lefauconnier.

From there, the exhibition follows the dizzying directions that electronic music has taken in the decades since, via all manner of artefacts and installations. As you make your way through the museum — due to pandemic restrictions, through a predetermined path with no backtracking — it’s one jolt after another, with audio commentary to fill in any blanks. (Bring your own headphones.) There’s a considerable spotlight on the U.K.’s contributions, which is not surprising given the country’s massive contributions to the development of electronic music. For longtime clubbers, the Haçienda club designs by Ben Kelly and Peter Saville will elicit a twinge of nostalgia, as will the section devoted to free raves and their backlash, complete with a selection of screaming newspaper headlines along the lines of evils of ecstasy and 11,000 youngsters go drug crazy.

Electronic music is a global phenomenon, of course, and the show includes such treats as an ‘imagined’ studio from the French synth deity Jean-Michel Jarre, Keith Haring–designed flyers for New York club nights, amazing large-scale rave photographer from Germany’s Andreas Gursky, that amazing video of Björk as a robot, a display of masks worn by notable artists and DJs — and that’s just scratching the surface. Pioneers like house godfather Frankie Knuckles, Detroit techno innovators Juan Atkins and dance music’s other foundational artists are represented, of course. And for product-design acolytes and/or drum-machine fans, the Visitor, a collaboration between Motor City maestro Jeff Mills and Yuri Suzuki of the design firm Pentagram, is of particular interest: The piece transfers the workings of the seminal Roland TR-909 and transfers them into a reflective futuristic desk for live performance.

“Electronic music needs to collaborate with design in order to present itself to the world.” — Gemma Curtain, The Design Museum

A pair of the exhibit’s pitstops boast From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers’ most full-bore moments. The Parisian vet Laurent Garnier put together a series of mixes that serve as electronic-music history lessons; the sets plays throughout the exhibit, but within 1024 Architecture’s Core installation, the music serves as the soundtrack for a mesmerizing audio-responsive piece consisting of 24,000 LED lights and 81 three-meter LED rods. (1024 Architecture also contributed the equally cool robotic sculpture Walking Cube, another audio-sensitive wonder of engineering.) Then there’s the exhibition’s final stop, courtesy of Adam Smith and Marcus Lyle, the creative directors for the Chemical Brothers: Set to the Chem’s joyous ‘Got To Keep On,’ their film, projected onto an immense screen, features phantasmagorically outfitted dancers frolicking their way through intense lighting effects. It’s as close to a rave as you’re going to get at a museum.

Daphne Oram’s Oramics machine, revisited by artist Peter Keene.

But before you reach that dénouement, make a beeline for the fascinating installation devoted to the partnership between the sui generis producer Aphex Twin and extreme-AV whiz Weirdcore, focusing on the creation of the mind-twisting visuals for Aphex Twin’s Collapse long-player. Novation has long played a role in Weirdcore’s methodology; attentive visitors might catch a clue regarding another upcoming collaboration.

The above is just a small sampling of what’s on tap at the exhibit — but for all that, From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers, as remarkable as it is, can’t quite replace the heady pleasure of feeling the bass ripple through your body in a sweaty basement party or sun-soaked festival, or the whirlwind thrill of being in the middle of a packed dance floor, nor is it meant to. It’s simply a fantastic show that pays homage to electronic music’s glorious past, and looks forward to its sure-to-be-wondrous future.

The exhibition is open to the public (advance booking required) and runs in London until 14th February 2021.

For more information, head to the Design Museum website.